Guy Perez Cisneros’ Speech at the United Nations, 1948

Published Thursday, December 10, 1998, in the Miami Herald

Here are excerpts from a speech delivered in Paris by Guy Perez Cisneros y Bonnel, Cuba’s chief delegate, on Dec. 10, 1948, as the U.N. Third General Assembly prepared to vote on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Cuba could not fail to participate in the choir of nations that wish to celebrate the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man. We feel great pride that the first, very modest draft officially submitted to serve as the basis for the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Man was written by Dr. Ernesto Dihigo, an eminent professor at the University of Havana and a member of the Cuban delegation.

Today that initiative [is presented] by the illustrious rapporteur of the Third Committee, Haitian Sen. Emile Saint-Lot, and by its president, Charles Habib Malik, Lebanon’s envoy to Havana. Cuba is deeply satisfied to see a Haitian as the bearer to humanity of the United Nations’s most valuable message. Haiti is precisely one of those privileged lands whose whole history is characterized by a heroic and constant effort to defend and enforce the rights of man. And Cuba is proud of having nominated as rapporteur [this] outstanding son of a French-speaking American nation, Haiti, a land in which the great Simon Bolivar, our Bolivar, found both moral encouragement and material aid to achieve his great task of liberation and freedom.

My delegation is duty bound to acknowledge the meritorious work of the Committee on the Rights of Man, which labored untiringly for two years under the inspiring leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt and wrote a truly valuable document that beautifully and forcefully expresses the highest aspiration of 20th Century man: the dawning of a world in which all human beings, freed from fear and want, will enjoy freedom of speech and freedom of opinion.

Another historic document that inspired the Third Committee’s work was the First Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, endorsed in Bogota by the nations of the Americas. Also, through the determined effort and great power of conviction of the Mexican delegate, Dr. Pablo Campos Ortiz, [was added] the important Article Nine [freedom from arbitrary arrest, detention, or exile], based on Mexico’s right of protection.

My delegation had the honor of inspiring the final text, which finds it essential that the rights of man be protected by the rule of law, so that man will not be compelled to exercise the extreme recourse of rebellion against tyranny and oppression. Further, this is an homage to France from my country, which greatly admired and watched the stages of its glorious résistance.

We are pleased that the social rights that are the main contribution of the 20th Century to this issue — just as legal rights were in the 19th Century — were treated in the Declaration with the importance they deserved.

We also thank the United Nations for its favorable reception of two Cuban amendments on the subject of labor that recognize the right of man to freely pursue his vocation and to receive a fair and satisfactory wage that will guarantee him and his family an existence befitting their human dignity.

My delegation will not forget the way in which the United Nations welcomed another of our initiatives: To include in the Declaration the right to the protection of one’s honor, a high moral concept rooted deep in the soul of every Hispanic person. And we cannot silence the fact that — through the joint efforts of France, Mexico, and Cuba — recognition was finally granted to those who belong to the only legitimate aristocracy: Creators, be they artists, writers, or scientists. They are entitled to the protection of the moral and material gains obtained through their scientific, literary, or artistic productions.

My country and my people are highly satisfied to see that the odious racial discrimination and the unfair differences between men and women have been condemned forever.

The Cuban delegation hesitated often before submitting its numerous amendments. It went ahead with the understanding that perfection and critical severity were among its duties. A delegation that represents a nation that proudly produced the Montecristi Manifesto was entitled to be demanding. [The manifesto outlined goals of Cuba’s independence movement and was drafted by Jose Marti and Maximo Gomez.]

The members of the Cuban delegation are deeply moved when — as they review the articles of the important Declaration that we will adopt in a few minutes — they recognize that all its provisions could have been accepted by that generous spirit who was the apostle of our independence: Jose Marti, the hero who — as he turned his homeland into a nation — gave us forever this generous rule: “With everyone, and for the good of everyone.”

Copyright © 1998 The Miami Herald

(Source: http://www.cubanet.org/htdocs/ref/dis/05200202.htm)

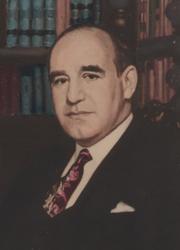

Gustavo Gutierrez y Sanchez

Cuban Lawyer, Jurist, Politician, Diplomat, Economist

Speaker of the House, 1940

(portrait by Valderrama)

1895-1959

Professor of International Law, School of Law, University of Havana-1919-1934.

Legal Counsel to Secretary of State-1925-29

Delegate- VI American International Conference, 1928

Delegate-Conference on Conciliation and Arbitrage, 1928

Secretary General-First Pan-American Conference of Municipalities, 1928

Delegate-Conference on Trademarks, Washington, 1929

Delegate-IV Pan-American Commercial Conference, 1931

Liberal Party – President-1930

Cuban delegate-IV Pan-American CommercialCongress, 1931

Secretary of Justice,1933

Member-House of Representatives, 1938-1942

Technical Advisor-Comission on Foreign Relations for the Senate, 193?

Technical Advisor-Comission for the Study of the New Constitution, 193?

Speaker of the House of Representatives, 1940-1941

Cuban delegation head and Sub-Committee President, United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) Atlantic City, 1943, 1944 and 1945.

G.A.T.T. (Tech. Dir., Cuban Delegation) Geneva-1947; (Head of Cuban Delegation) Geneva, Petropolis-1950, 1954

Head of Cuban delegation, (Gatt) Havana Charter, 1948

President-Junta de Economia de Guerra, 1942

President-Cuban Maritime Commission, 1942-43

Ambassador to the United Nations (Security Council)1948

President-Cuban Delegation, General Assembly, 1949

Technical Director/Secretary/President-National Junta of Economy (Junta Nacional de Economia) 1948-1953

President-United Nations Economic Committee, 1951

Minister of Finance (Ministro de Hacienda) 1953-1955

Special Envoy-O.A.S. Conference of the Presidents, Panama, 1956

President-Cuban Nuclear Energy Commission, 1956

President-Ministerial Commission for Tariff Reform, 1958

Minister of Economy (a.k.a. Ministro Presidente-Consejo Nacional de Economia/National Board of Economy, 1955-1959.

“The Declaration” (1948)

John P. Humphrey prepared the first draft for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1947. He states in the Human Rights Quarterly, “Memoirs of John P. Humphrey, the First Director of the United Nations Division of Human Rights,” published by The John Hopkins University Press, Vol. 5, No. 4 (November,1983), pp. 387-439, “I was no Thomas Jefferson and, although a lawyer, I had had practically no experience drafting documents. But since the Secretariat had collected a score of drafts, I had some models on which to work. One of them had been prepared by Gustavo Gutierrez (Sanchez) and had probably inspired the draft Declaration of the International Duties and Rights of the Individual which Cuba had sponsored at the San Francisco Conference.” (pp. 406). This, in fact, was correct. Dr. Gutierrez wrote a book entitled “La Carta Magna de la Comunidad de las Naciones in 1945, where the document mentioned above originated. In addition, his draft for the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was chosen as one of seven drafts presented by “private parties.”

In 2008 Indiana University Press published “Human Rights at the UN, The Political History of Universal Justice,” written by Roger Normand and Sarah Zaidi. Under the heading Chapultapec: Rebellion or Reaction? the authors write, “The dissatisfaction of Latin American governments found expression in an extraordinary meeting in February 1945 at Chapultapec Castle in Mexico City, where twenty Latin American countries and a large delegation from the United States participated in the Inter-American Conference on Problems of War and Peace. They reviewed the Dunbarton Oaks proposals in details and introduced 150 draft resolutions urging substantial reforms, many addressing human rights. (49)”…”Cuba submitted two detailed proposals for consideration, a “Draft Declaration of the International Rights and Duties of the Individual” and a “Draft Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Nations. (50)” These two drafts were written and published by Dr. Gustavo Gutierrez in a book entitled La Carta Magna de la Comunidad de Naciones. Please see blog entry for December, 2008 entitled “The Magna Carta of the Community of Nations, 1945.”

Gustavo Gutierrez was part of the large Cuban delegation at the Chapultapec Conference.

Normand and Zaidi continue. “These proposals were reintroduced in San Francisco and during the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Latin America’s significant intellectual production supporting human rights is a major reason the region has been called “the forgotten crucible” of universal human rights. (51) Latin American jurisprudence was particularly well suited to bridging cultural divides in human rights by linking civil and political rights with economic and social rights…(52) With their dominant voting bloc, the Latin American countries would play a significant role in advancing human rights throughout the UN process.”

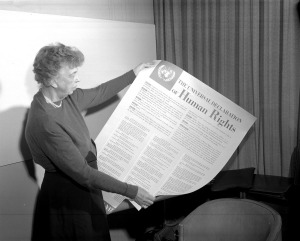

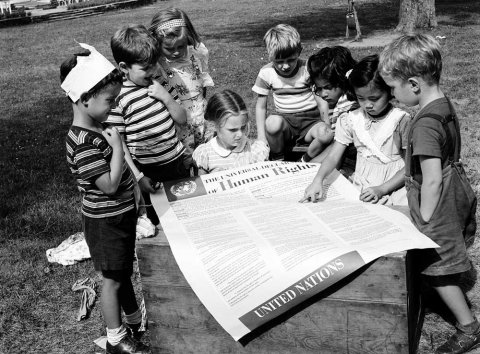

In 1950, on the second anniversary of the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, students at the UN International Nursery School in New York viewed a poster of the historic document.

“…These civil society proposals for human rights found strong support among non-European states, especially in Latin America. (96) Many of these states had recently written human rights into their own constitutions, and their delegations included prominent jurists whose primary focus was to advance human rights. Peace and security, they argued, could be based only on the protection of human rights, not just traditional civil and political rights but also economic and social rights. Chile, Cuba and Panama resubmitted the proposal for binding international bill of rights from the Chapultapec Conference.”

Referring to the statements made in the above paragraph, it is interesting to note here that Gustavo Gutierrez had provided the first draft for the creation of the Cuban Constitution of 1940 and was considered among Latin America’s most renowned jurists. For more information regarding this topic please see blog entries;

1) “New Constitutión Project”, 1940. Blog entry April, 2009

2) “Proyecto Nueva Constitución, 1940”, # 1, #2 and #3. Blog entry September, 2009

3) “Pioneer of 1940 Constitution” by Enrique Llaca. Blog entry June, 2008

“…The main challenge to the Big Three’s (U.S.A., the U.K. and the U.S.S.R.) human rights strategy came from the insistence of Latin American countries, supported by civil society groups, on proposing a binding international bill of rights. With support from Cuba, Chile and Mexico, Panamanian foreign minister Ricardo Alfaro put forward the American Law Institute’s draft bill of rights.”

“…The idea of an international bill of human rights received particular attention. The UN Secretariat staff noted that as of 1946, it had received twelve different drafts submitted by the delegations of Panama, Chile, Cuba, and the American Federation of Labor as well as private drafts from Hersch Lauterpacht of Cambridge University, Alejandro Alvarez of the American Institute of International Peace, Prof. Frank McNitt of the faculty of Southwestern University, and H. G. Wells. (6)”

Gustavo Gutierrez’ draft was among this group of seven “private” drafts mentioned above and at the top of this entry, including those by Wilfred Parsons and Irving A. Isaacs. Dr. Gutierrez’ “private” draft was the one proposed by the Cuban delegation in San Francisco just like the draft introduced by Chile’s delegation could have been that of Chilean, Alejandro Alvarez.

(Source: http://drgustavogutierrez.blogspot.com/2010_12_01_archive.html)